II. Spirituality

By studying iconography we naturally reach the theme of spirituality. We have

a better documentation on Egyptian and Greek considerations about religion since

both texts and paintings have been studied by many scholars ; we know less about

Mesopotamian and Assyrian mental representations, but we think that even this

little knowledge might be enough to parallel the signification of their board-games

with those of other civilisations. First of all, the context of excavations

of those objects is an evidence of the continuity of a certain meaning ; for

us it is clear that the board-game was a way of interpreting signs for those

who were scared about their life after death ; many boards have been discovered

in tombs with the diagram in direction of the floor.

It is the case for the Ur boards, for some of the Mehen examples,

and for some of the reversible boards found in Egyptian tombs on which

we can notice that the hieroglyphs are readable when the Game of Thirty squares

design is facing down. We may interpret this fact as an endeavour to simulate the communication made possible by the board for

users between the world of life and a mysterious netherworld. We know that in

the religious conception of Mesopotamian people, Hell was a land from which

you could not come back, located far in the West. It is the case for the Ur boards, for some of the Mehen examples,

and for some of the reversible boards found in Egyptian tombs on which

we can notice that the hieroglyphs are readable when the Game of Thirty squares

design is facing down. We may interpret this fact as an endeavour to simulate the communication made possible by the board for

users between the world of life and a mysterious netherworld. We know that in

the religious conception of Mesopotamian people, Hell was a land from which

you could not come back, located far in the West.

We may interpret some of the designs of their board-games

as an expression of the idea that the dead needed help in his dangerous travel

in that unknown direction symbolised in the design of the board by the choice

between two possible directions to take out the pieces at the end of the game.

Because they were almost alike, they could have represented a kind of divination

to interpret the best way to go from one world to the other.

The decoration of the boards from Ur shows some symmetry in the symbols

and perhaps this “geometry” was in relation with some religious beliefs. It

is interesting to compare them to those coming from Egypt with their multiplication

of symbolic meanings at the end of the board. Because they were almost alike, they could have represented a kind of divination

to interpret the best way to go from one world to the other.

The decoration of the boards from Ur shows some symmetry in the symbols

and perhaps this “geometry” was in relation with some religious beliefs. It

is interesting to compare them to those coming from Egypt with their multiplication

of symbolic meanings at the end of the board.

However, at the same time the board from Egypt were much more

simple in their decoration and the symbols are apparently more connected with

the rules of the game than with its hypothetical religious meaning. Nevertheless,

in both civilisations those boards could be seen as an expression of the travel

of the dead soul through the netherworld. The house of Horus, the thirtieth

square, in the Game of Senet was connected with the idea that after having been

justified by the judges, the soul of the deceased was taken to heaven by a falcon

in the solar-ship of Re-Amun, and even the name of the

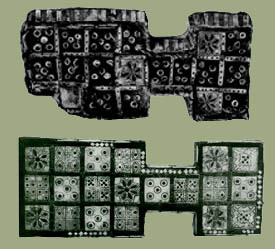

game passing is one of the oldest cultural particularity of the Egyptian tradition.One good example is given by the thirty

squares made in steatite inlaid with lapis-lazuli, which has been analysed by

Needler . We do not have the board which was probably made of

wood but we can see with the squares the attention put in the realisation of

luxurious boards. Kendall has developed this idea with very persuasive evidence and sums it up

as follows : The encounters of a player with his opponent were seen as the encounters

of his soul with the evil or inimical forces that lurked in the nether regions,

and his victory was the attainment of the happy afterlife. The house of Horus, the thirtieth

square, in the Game of Senet was connected with the idea that after having been

justified by the judges, the soul of the deceased was taken to heaven by a falcon

in the solar-ship of Re-Amun, and even the name of the

game passing is one of the oldest cultural particularity of the Egyptian tradition.One good example is given by the thirty

squares made in steatite inlaid with lapis-lazuli, which has been analysed by

Needler . We do not have the board which was probably made of

wood but we can see with the squares the attention put in the realisation of

luxurious boards. Kendall has developed this idea with very persuasive evidence and sums it up

as follows : The encounters of a player with his opponent were seen as the encounters

of his soul with the evil or inimical forces that lurked in the nether regions,

and his victory was the attainment of the happy afterlife.

A loss on the other hand, would seem to have meant utter annihilation and

death without redemption. Now, more than ever, senet sets were buried with the

dead not only for amusement but, more importantly perhaps, as symbols of their

hoped-for resurrection and the difficult road to Paradise that was thought to

lie before them. We know the great place devoted to moral rules in the

ancient Egyptian society; we all have in mind the image of the pair of scales

deciding whether the heart of the deceased was able to enter paradise after

his judgement in front of truth and justice symbolised by Maât.

We also know that from the New Kingdom, texts about Senet began to take the

place of the actual board, which up to then had usually been placed in tombs

to accompany the deceased on his journey to paradise. We linked up these facts

with the 17th chapter of the Book of the Dead, a sort of compilation

of all the magical spellings useful to the dead in order to guarantee his success.

However, we known that a game of chance always come with some people trying

to deny its reality and necessity ; considering this fact, we think that a very

deep mental structure of Egyptian religion and spirit comes to light with what

we know of Senet. By the time of the New Kingdom, Senet was probably used in

every single social class. Good players could have represented the cleverest

part of it, or in religious conception the purest.

Interestingly, we know that for Egyptians amulets and spellings

were of great use to go over the final judgement. We do not know whether it

is the cast of the priest which introduced Senet in the ritual of eschatology

or if it must be seen as an eccentricity of some addictive players victims of

their superstition or of their love for board games. Both might be the expression

that Senet could have been of great comfort for those who knew how to play well

or even how to cheat, to think they could reverse decisions of gods and forced

them to admit their soul in paradise. It must have brought ancient Egyptians

great reassurance to act out and divine the afterlife and know they might still

live with Re in heaven after death no matter what sins they had committed in

life. As Piccione sums up : At the most the game indicates that ancient Egyptians

believed they could join the god of the rising sun, Re-Horakty, in a mystical

union even before they died. At the least, senet shows that, while still

living, Egyptians felt they could actively influence the inevitable afterlife

judgement of their soul. Interestingly, we know that for Egyptians amulets and spellings

were of great use to go over the final judgement. We do not know whether it

is the cast of the priest which introduced Senet in the ritual of eschatology

or if it must be seen as an eccentricity of some addictive players victims of

their superstition or of their love for board games. Both might be the expression

that Senet could have been of great comfort for those who knew how to play well

or even how to cheat, to think they could reverse decisions of gods and forced

them to admit their soul in paradise. It must have brought ancient Egyptians

great reassurance to act out and divine the afterlife and know they might still

live with Re in heaven after death no matter what sins they had committed in

life. As Piccione sums up : At the most the game indicates that ancient Egyptians

believed they could join the god of the rising sun, Re-Horakty, in a mystical

union even before they died. At the least, senet shows that, while still

living, Egyptians felt they could actively influence the inevitable afterlife

judgement of their soul.

In the same range of idea, we can try to analyse the meaning

of board-games representations in Greek paintings. About more than a hundred

of ceramics, be they black or red-figures (and even bilingual ones), use the

topic of the confrontation of two Greek warriors around a board-game. Most of

them occur in a war context and represent Achilles and Ajax absorbed

in the game bilingual amphora, sometimes with Athena between them . Iconographic

details are of great value and a very close research ought to be done on this

subject. In that purpose, a large number of scholars tried to interpret this

topic in relation to what we know of epic or tragic literature. The other side

of those ceramics represent diverse motifs and is also useful in our attempt

of comprehension. In most of them, a relation could be seen with the spiritual

meaning involved in the practice of gaming. For example, Athena can be

seen as the goddess of war as well as of cleverness and strategy. Dionysos is

related to ritual festivities, the signification of the tragedy in archaic Greece,

death of course, but also victory in war. In the same range of idea, we can try to analyse the meaning

of board-games representations in Greek paintings. About more than a hundred

of ceramics, be they black or red-figures (and even bilingual ones), use the

topic of the confrontation of two Greek warriors around a board-game. Most of

them occur in a war context and represent Achilles and Ajax absorbed

in the game bilingual amphora, sometimes with Athena between them . Iconographic

details are of great value and a very close research ought to be done on this

subject. In that purpose, a large number of scholars tried to interpret this

topic in relation to what we know of epic or tragic literature. The other side

of those ceramics represent diverse motifs and is also useful in our attempt

of comprehension. In most of them, a relation could be seen with the spiritual

meaning involved in the practice of gaming. For example, Athena can be

seen as the goddess of war as well as of cleverness and strategy. Dionysos is

related to ritual festivities, the signification of the tragedy in archaic Greece,

death of course, but also victory in war.

The character of Herakles is interpreted usually in keeping with the fight

against chaos and the organisation of civilisation (gigantomachy or battles

against Amazons). A very interesting explanation of this popular motif is given

by J. Boardman. The first element of his demonstration concerns the fact that

Ajax became an honorary Athenian with Salamis annexed and the Salaminioi part

of the citizen body, which was going to give its name to one of the new tribes

of the democracy. Before that, Peisistratos’ return to Attica in 546 had been

an embarrassing and shaming episode for an Athens which had long been free from

the tyrant’s family.

The author thinks that Exekias might have used this episode related by Herodotus

in relation with the idea that the two heroes Achilles and Ajax had been surprised

in the Troy battlefield by a sudden attack while they were absorbed in their

game. The other side of the ceramic shows the Dioskouroi which are well known

as symbols of anti-tyrannical spirit. It could, then, be some sort of political

propaganda as Boardman says :

"Pride was injured and the best balm to sore pride is the

example of others and betters who had suffered in the same way but survived.

If Exekias’ attitude to tyranny in Athens was anything like we have suspected

from his use of other myth scenes and heroic figures, he would have been very

likely to promote a mythical parable-normal procedure in commenting on a contemporary

dilemma-which might both comfort and give warning that, in the face of tyranny

and defeat, survival lies in the alert.

For other commentators the explanation could be linked with divination (heroes

seen as able to discuss with the gods to discover their fate), with mythology

(as part as the Troyan cycle) or with virtue and education given by heroic

examples. We do not know much about Greek board-games and paradoxically we have

more literary evidence than archaeological evidence. Nevertheless it is possible

to interpret the inscriptions coming with the representation, along with the

context and what we know about the presumed fate of these two heroes ; for us

there is a possibility that artists wanted to express the tragic quality

of their life, and at the same time the great memory of their acts, by the use

of their confrontation with a board-game.

Thus, Greek artists might have been influenced by Egyptian considerations on

this topic, and might merely have changed the meaning, in order to adapt it

to Greek conceptions of death and memory. This way, these scenes become an expression

of the tragedy of everybody’s fate symbolised by Chance and ignorance,

and of the attempt of Greek mythological heroes to compare their forces with

the Gods. However it is worth noticing that the context in which the Greek and

Egyptian representations of players were born is really different. In the latter

it is the ritualistic and peaceful impression which dominates, whereas with

the Greeks the clothes, the weapons, and the tension perceptible between the

players confer a much more violent expression to those scenes.

Remarks : There is much to say about relations between religion and

board games, if we consider that the latter are made in the purpose of simulating

both the real life and the cosmic forces, which are in charge of organising

it.

It is for us of great value to research in different civilisations all the

details we could find about the religious meanings, involved in board-games,

for two opposite reasons : because they teach us a lot about the representation

of the relations between human beings and their gods and the fear of death

and judgement related to each civilisation. Moreover, they show us that

maybe ancient people were not that much scared of life after death and that

they could play with their judgement and even cheat. These practice could even

be an expression of how they had succeeded in taking their fate into their own

hands thanks to the help of board games.

|

^

top |

|

Figure 1:

Loud,G.

1939. The Meddigo ivories, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Figure 2:

Wooley, L.

1934. Ur excavations, Vol II, The Royal Cemetery ; p. 274, fig. 95-98, 158,

221, London.

Figure 3:

Gadd, C. J.

1934. An Egyptian Game in Assyria, Iraq I; p.43 et ss.

Figure 4:

De Kainlis, A.

1942. « Un jeu assyrien au Musée du Louvre » in Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie

orientale T.

XXXIX, Paris ; p. 19 à 34.

Figure 5:

Swiny, S.

1976. « Offering tables » from Episkopi Phaneromeni, in Report of the Department

of Antiquities Cyprus, Nikosia.

1980. Bronze age Gaming Board from Cyprus, in Report of the Department of Antiquities

Cyprus, Nikosia.

Dunand, M.

1958. Fouilles de Byblos. 1933-1938, Paris.

Fugmann, E.

1958. Hama. Fouilles et recherches 1931-1938. Vol III, Copenhague.

Figure 6:

Nougayrol, J.

1945. « Textes hépatoscopiques d’époque ancienne » in Revue d’Assyriologie et

d’Archéologie orientale, vol. LX, Paris ; p. 65à 76.

1947. « Textes et documents figurés » in Revue d’Assyriologie et d’Archéologie

orientale, vol. LXI, Paris.

Figure 7:

Push, E. B.

1979-Das senet-brettspiel im alten Agypten, Munich.

Figure 8:

Wooley, L.

1934. Ur excavations, Vol II, The Royal Cemetery ; p. 274, fig. 95-98, 158,

221, London.

Figure 9:

Needler, W.

1953. A Thirty squares draught-board in the Royal Ontario Museum, Journal of

Egyptian Archeology.

Figure 10:

Piccione, P. A.

1984. Journal of Egyptian Archeology 70.

1980. In searching of the meaning of Senet, in Archeology 33, New York ; p.55

à 59.

David, F.N.

1962. Games, Gods and Gambling, Londres.

Figure 11:

Beazey, J. D.

1928. Attic Black-figure : a sketch, Londres.

1986. The development of Attic black-figure, revised ed.; chap. 6 : Ekexias.

Moore , M. B.

1980. Exékias and Telamonian Ajax, AJA 84.

Boardman, J.

1978. Exekias, A.J.A 82.

Boardman, J.

1988. Athenian black-figure vases, Thames and Hudson, Cambridge.

Thomas, K. N.

1985. Three repeated mythological themes in attic black-figure vase painting.

Figure 13:

Salomé, M. R.

1980. Code pour l’analyse des représentations figurés sur les vases grecs, Centre

de recherches archéologiques, C.N.R.S.

Brown. Thomson, D. L.

1976. Exékias and the brettspieler, Archéologie classique XVII. Figure 15:

Kendall, T.

1978. Passing through the netherworld :The meaning and play of senet, an ancient

Egyptian funerary game, The Kirk game company, Belmont.

Caillois, R.

1955. Structure et classification des jeux, in "Diogène".

1958. Les jeux et les hommes, Paris.

Erdös, S.

1986. Les tabliers de l’Orient ancien, maîtrise d’archéologie, Université Paris

I.

Jouer dans l’Antiquité.

1992. Catalogue de l’exposition du Musée archéologique de la Vieille Charité,

Centre de la Vieille Charité, Marseille. (plate II, fig. 7)

Lexikon der Ägyptologie, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden.

Un siècle de fouilles françaises en Égypte 1880-1980. 1981.

Catalogue de l’exposition de l’école du Caire, IFAO, Le Caire

Murray, A.

1952. History of board-games other than chess, Clarendon Press, Oxford

Amandry, P.

1950. La mantique apollinienne à Delphes, Athènes.

Brewster, P.G.

1957. The earliest history of games : some comments, Acta orientalia, XXIII.

1960. A Sampling of games from Turquey, « East and West » n.s XI, I, March

Buchholz, H.-G.

1987. « Brettspielende Helden » in Siegfried Laser, Sport und Spiel (Archeologica

Homerica), Göttingen

De Voogt, A. J.(éd.).

1995. New Approaches to Board-games research : Asian origins and future perspectives,

International Institute for Asian studies, Leiden.

Dussaud, R.

1914. Les civilisations préhelleniques dans le bassin de la Mer Egée, Geuthner,

Paris.

Huizinga, J.

1951. Homo Ludens : Essai sur la fonction sociale du jeu, Paris.

Montet, P.

1955. Le jeu du Serpent, Chronique d’Égypte 30

Naville, E.

1886. Das ägyptische Todtenbuch der XVIII. Bis XX. Dynastie, aus verschiedenen

Urkunden zusammengestellt. 3 vol., Berlin.

Neugebauer, O.

1969. The Exact sciences in Antiquity. 2nd Edition, New York.

Oppenheim, A. L.

1965. "Mesopotamian divination" in Rencontres Assyriologiques : «La divination

en Mésopotamie ancienne », vol XIV, Strasbourg.

Ancient Greek Art and Iconography, edited by Warren.G.Moon, University of Wisconsin,

1983.

Catalogue de l’exposition sur les jeux et les sports dans le monde Antique à

l’Institut pédagogique, Paris, 1954.

De Merzenfeld, D.

1954. Inventaire commenté des ivoires phéniciens et apparentés, découverts dans

le Proche- orient. Paris.

Desroches-Noblecourt, C.

1985. Le grand pharaon Ramsès II et son temps, Catalogue de l’exposition de

Montréal.

Egypt’s golden age : The Art of living in the new Kingdom.

1982. Catalogue de l’exposition du Musée of Fine Art, Museum of Fine Art, Boston.

Hayes, W. C.

1953. The Scepter of Egypt, Cambridge.

Leclant, J (éd.).

1978. Le temps des pyramides, vol. II, Paris.

Montet, P.

1925. Les scènes de la vie privée dans les tombeaux égyptiens de l’Ancien Empire,

Strasbourg.

Schäfer, H.

1974. Principles of Egyptian Art, Oxford.

Van Buren, D.

1944. The Symbols of the gods in Mesopotamian Art, Rome.

Sources for publication of old Board-games.

Albright, W. F.

1938 The Archeology of Tell Beit Mirsin, vol II : the Bronze Age, in Annal of

the American Schools of Oriental research, vol. XVII, New Haven.

A set of Egyptian playing pieces and dices from Palestine, in Mizraim, vol.

I, New York, p. 130 à 134.

Ayrton, E.R, et Loat, W.L.S.

1911. Pre-dynastic cemetery at El-Mahasna, London ; pl. XVII.

Baker, H.

1966. Furniture in the Ancient World, New York ; p.59, fig. 60.

Blackman, M.A.

1920. Journal of Egyptian Archeology 6.

1924. The Rocks Tombs of Meir , London, pl. IX.

Bottéro, J. 1956.

Deux curiosités Assyriologiques, in Syria 33, Paris ; p. 17-35.

Brumbraugh, R. S.

1975. The Knossos game board , A.J.A 79 .

Bruyère, B.

1930. Rapport sur les fouilles de Deir el-Medineh.

Contenau, G.

1947. Manuel d’archéologie orientale IV, Picard, Paris.

Courtois ,J.C.

1986. Enkomi et le bronze récent à Chypre, Nicosie.

Carnarvon , Carter, H.

1912. Five years explorations at Thèbes, Oxford.

David, A. R.

1979. Toys and Games from Kahun in the Manchester Museum collection, in Glimpses

of Ancient Egypte, Warminster.

De Morgan, J.

1905. Délégation en Perse : recherches archéologiques, tome VII, Paris.

Dever, W. G.

1976. The beginning of the Middle Bronze Age in Syria-Palestine, New York.

De Mecquenem, A.

1905. Mémoire de la délégation de Perse, vol. VII, Paris ; p. 104 à 106.

Drioton, E.

1942. « Un ancien jeu copte » in Bulletin de la société d’archéologie copte,

vol. VI, Paris, p. 171.

Dunham, D.

1950. El-Kurra (R.C.K I), Cambridge ; fig. 24a.

1978.

Zawiet el-Aryan, Boston ; fig. 72.

Ellis, R. S. et Buchanan, B.

1925. «An old Babylonian Game board with sculptured decorations » in Journal

of Near Eastern studies, vol. XXV n° 3, 1925 ; p. 192 à 201.

Emery, W. B and Kirwan, L. P.

1938. The Royal Tombs of Ballana and Qustul.

Emery, W.

1954. Great Tombs of the First Dynasty, v. II, London, pp. 29, 31, fig. 11,

pl. XXII ; pp. 56, pl. XXIX.

Harrak, A.

1987. Another specimen of an Assyrian game, in Archiv für Orientforschung 34,

pp. 56-57.

Hassan, S.

1975. The Mastaba of Neb-Kaw-Her, vol. I ( Excavations at Saqqara, 1937-1938

), Le Caire, p. 23, fig. 7, 12.

James, T.G.H.

1974. Corpus of hieroglyphic inscriptions in the Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn ;

p. 23, n° 278.

Jéquier, G.

1921. Les frises d’objets (MIFAOA 47), Le Caire, 1921 ; p.262, fig. 689.

Junker, H.

1940. Gîza IV, Vienne.

Lauer, J. P.

1976. Saqqara, London ; fig. 69.

Macalister

1912. The Excavation of Gezer, vol. II et III, Londres.

Macramallah, R.

1940. Un cimetière archaïque de la classe moyenne du peuple à Saqqarah, Caire,

Imprimerie Nationale, pl. XLIX, 2.

Meyer, J. W.

1982. « Lebermodell oder Spielbrett » in Kamid el-Löz 1971-74, Bonn ; p. 53

à 79.

Oppenheim, M. F. von.

1962. Tell halaf. Die Kleinfunde aus Historischer Zeit, Berlin, 1962 .

Parrot, A.

1956. Mission archéologique de Mari, vol. II : le Palais.

Petrie,F.

1900. Sir. Royal tombs of the Earliest dynasties, Part. I, London p.23 ;Part.

II (1901), p.36, fig. XIII, 93 ; XIV, 100 ; XXIII, 194 ; XXXII, 34, 71 ; XXXIV,

1- 17 ;XXXV, 5, 6, 73.

1895. Naqada and Ballas, pp. 14, 35, pl. VII, 1, 2.

1892. Medum, London ; pl.XIII. 1902. Sedment, London. 1927.

Objects of Daily Use, in BSAE 42, London.

Piccione, P. A.

1990.Mehen, Mysteries and Resurrection from the coiled serpent, in JARCE 27,

1990.

Piperno , M. et Salvatori, S.

1983. « Recent results and new perspectives from the research at the graveyard

of Shar-i Sokhta, Sistan, Iran » in Annali vol. 43.

Pritchett, W. K.

1968. Five lines and IG2, 324. In : Californian Studies in Classical Antiquity

1.

Quibell, J. E.

1913.Excavations of Saqqara : vol. V : the Tomb of Hesy, 1911-1912, Le Caire.

Riefstahl, E.

1968. Ancient Egypt glass and glazes in the Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn ; p. 21,

fig. 19, 96.

Scott, F.

1944. Home life of the Ancient Egyptians, New York; fig. 31.

Shore, A. F.

1963. A « Serpent » Board from Egypt. The British Museum Quartely., vol. XXVI,

n° 3-4.

Shorter, A.

1938. Catalogue of the Egyptian Religious Papyri in the British Museum, London.

Simpson, W.K.

1976. The Mastabas of Qar and Idu : G 7101et G 7102, Boston, Museum of Fine

Arts, p. 25, pl. XXIV, b ; fig. 38.

Tait, W. J.

1982. Game boxes and accessories from the tomb of Tut’ankhamun, Griffith Institute,

Oxford.

Université de Chicago.

1952. Expedition of Saqqarah (Prentice Duell and al.), The Mastaba of Mereruka

(Oriental Institute Publications XXXIX) Part. II, Chicago ; pl. 172.

Van Buren, E.D.

1937. A gaming board from Tell Halaf, Iraq IV.

Van de Walle, B.

1930. Le Mastaba de Neferirtenef, Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, Bruxelles ;

p. 55, fig. 6.

Wilkinson, C.

1874. Popular account, vol. I, London, ; p. 192, fig. 208.

|

^

top |